Interestingly, I'm in the middle of this process right now. My agent was curious what my plans were for Garnet after I deliver DEAD SEXY in late-May, so I started crafting synopses/proposals for the next books currently cleverly titled: GARNET BOOK III, and GARNET BOOK IV.

There are two times in which you may be required to write a synopsis. First, when you finish your first novel and begin the process of selling it, and, second, when you're selling the idea of the next novel to your existing publisher/editor. I have been fortunate that the majority of my synopsis writing has been in category two.

I don't imagine that's very typical, and it gives me a slightly skewed sense of how the proposal process works. Still, I've had a fair amount of experience writing synopses, and it's actually an exercise I kind of enjoy. I know, I’m sick. This is news?

I have a really great book that I would like to suggest to any of you who are sitting down to struggle with the proposal process. It's called YOUR NOVEL PROPOSAL: FROM CREATION TO CONTRACT by Blythe Camenson and Marshall J. Cook (Writers Digest Press, 1999). Chapter Six is the pertinent section and is worth, in my opinion, the entire cover price of the book (not to mention Amazon.com offers used versions much cheaper.)

The most important thing to remember about writing synopses is what they're used for. They are a shorthand for agents and editors to get a sense of what your story is about. Herein, lies the key. Just as in writing a short story, you need to lay out the conflict in the first sentence (or, at the very least in the first paragraph.) By conflict, I don't just mean the wham, bam exciting plot element. I mean the emotional conflict. What is it that compels your hero or your heroine to take on this adventure? What does s/he stand to lose? To win? Why is this story going to change the protagonist's life? What does your character want? To quote Philip Martin's THE WRITER'S GUIDE TO FANTASY LITERATURE: FROM DRAGON'S LAIR TO HERO'S QUEST, "As Kurt Vonnegut famously said, a story should start with a character who wants something, even if it’s just a glass of water."

In a synopsis you need to lay that stuff bare. Just spell out what is motivating your hero/ine. Then (and here's the part that's much tougher when you're distilling a 400 page manuscript into a ten page synopsis) tell us only what you need in order to explain how that person either gets or doesn't get what they want over the course of the novel. Sub-plots can be cut. Major plot points can be cut – but only if they don't reflect an answer to the question of how you character gets (or doesn't get) what they want.

Also, in a synopsis, there is not point to being coy. Just tell us what happens, no need to be clever or mysterious – particularly about the ending. Endings must be revealed, and they should give the reader a sense of resolution. Synopses are the opposite of "show, don't tell" – they're all about the telling.

Yet, with all this telling, it's very easy for a synopsis to start sounding repetitive, "and then, and then." You also need to stay on top of your storytelling game. Find a way to make what you're saying reflect the tone of the novel. Luckily, I write chatty, sassy novels, so my synopses can have clever asides or other kinds of sarcastic comments – which may be why I find the writing of them much more fun than most people do.

Ah, yes, there are a couple of rules to writing synopses that I forgot to mention. Regardless of how the book is written, synopses must be in third person (he, she, it) and in present tense (is, am, are). There's also some formatting requirements, but you can find those in books like the one I mentioned above.

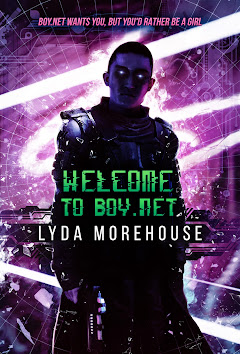

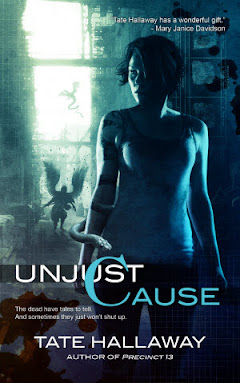

If you want to see an example of a synopsis, I have one on-line (for my alternate personality, so I guess the cat’s out of the bag) here: Messiah PDF (It's in PDF format.)

No comments:

Post a Comment